The terminal object as an identity for multiplication

In any category, B is a product of B and the terminal object.

Calculating the graphs A x Y

Given B1 <-(f1)<- X ->(f2)-> B2 (?), a graph of the form A x Y has a structure similar to that of the graph X. The dots of A x Y are divided into two sorts so that in one of them there are no targets and in the other there are no sources. Furthermore, the arrows of A x Y are the pairs of arrows <a, y> where a is an arrow of A and y is an arrow of Y. Since A has only one arrow, we conclude that A x Y has precisely as many arrows as Y has. And the number of dots of A x Y is twice the number of dots of Y, since A has two dots.

(some other stuff here, feel twisted in my mind)

The distributive law

In a category C, for any three objects A, B1 and B2 that has sums and products, a ‘standard’ map A x B1 + A x B2 -> A x (B1 + B2) and the standard (only) map 0 -> A x 0 have inverses, then the distributive law holds in C, or say that the category C is distributive. This is the case in all the categories discussed in the former discussions.

In categories in which the distributive law doesn’t hold, the use of ‘sum’ for that construction is often avoided; it is often called ‘coproduct’ instead, which means ‘dual of product’.

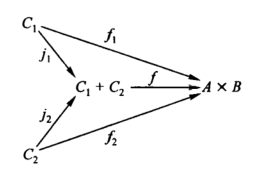

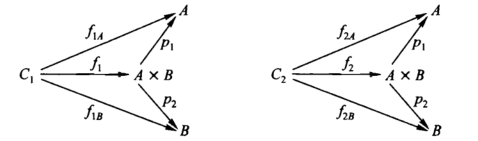

A map from a coproduct of two objects to a product of two objects is ‘equivalent’ to four maps, one from each summand to each factor. Since its domain is coproduct, we know tht a map f from C1 + C2 to A x B is determined by its composites with the injections of C1 and C2, and can be denoted f = [f1; f2] where f1 and f2 are the result of composing f with the injections of C1 and C2 into C1 + C2.

Furthermore, each of the maps f1 and f2 is a map into a product, and thus has two components, so that f1 = <f1A, f1B> and f2 = <f2A, f2B>.

The end result is that f can be analyzed into the four maps: C1 ->(f1A)-> A, C1 ->(f1B)-> B, C2 ->(f2A)-> A, C2 ->(f2B)-> B, and, comversely, any four such maps determined a map from C1 + C2 to A x B given by f = [f1A f1B; f2A f2B].

This analysis can be carried out more generally, for coproducts and products of any number of objects. For any object C1, …, Cm and A1, …, An, denote product projections by A1 x … x An ->(pv)-> Av and sum injections by Cu ->(ju)-> C1 + … + Cm. Then for any matrix [f11 f12 … f1n; …; fm1 fm2 … fmn] where fuv: Cu -> Av, there is exactly one map C1 + … + Cm ->(f)-> A1 x … x An satisfying all the m x n equations fuv = pv◦f◦ju.

A general distributive law: if B1, B2, …, Bn and A are objects in any category with sums

and products there is a standard map A x B1 + A x B2 + … + A x Bn -> A x (B1 + B2 + … + Bn).

The general distributive law says that this standard map is an isomorphism.

In the case of n = 0 the domain of this map is an initial object, and the map itself is the unique map 0 -> A x 0 which is obviously a section for the product projection A x 0 -> 0.

Matrix multiplication in linear categories

Definition: A category with zero maps in which every ‘identity matrix’ is an

isomorphism is called a linear categroy.

For linear categories having zero maps, for any two object X, Y there is a special map from X to Y called the zero from X to Y, denoted by 0XY. The fundamental property of a zero map is that composed with any other map it gives another zero map. Thus for any map Y ->(g)-> Z, the composite g◦0XY is the zero map 0XZ. Similarly, for any map W ->(f)-> X, 0XY◦f = 0WY. The existence of zero maps has as a consequence that we can define a prefered map from the coproduct X + Y to the product X x Y, f = [1X 0XY; 0YX 1Y]: X + Y -> X x Y. This map is called the ‘identity matrix’.

In a linear category, since every identity matrix is an isomorphism, we can ‘multiply’ any matrices A + B ->(f)-> X x Y and X + Y ->(g)-> U x V. [fAX fAY; fBX fBY][gXU gXV; gYU gYV] = [gXU gXV; gYU gYV]◦[1X 0XY; 0YX 1Y]-1◦[fAX fAY; fBX fBY]

The ‘product’ is another matrix since it is nothing but the composite A + B ->(f)-> X x Y ->(alpha)-> X + Y ->(g)-> U x V where alpha is the assumed inverse of the identity matrix.

Sum of maps in a linear category

If A and B are any two objects in a linear category, we can add any two maps from A to B and get another map from A to B. For example, take X = U = A, Y = V = B, then [1AA f; 0BA 1BB][1AA g; 0BA 1BB] = [1AA h; 0BA 1BB] for exactly one map h: A -> B. The sum of f and g is now defined to be this map h, so that f + g is uniquely determined by the equation.

The associative law for sums and products

The associative law for multiplication of objects is true in any category with products. The sum of three objects can be defined in a similar way as the sum of two objects. The universal mapping property will now involve three injection maps and for any three maps from B1, B2, and B3 to any object X, Bi ->(fi)-> X {i = 1,2,3} there is a unique map B1 + B2 + B3 ->(f)-> X, which can be denoted by f = [f1; f2; f3] such that fj1 = f1, fj2 = f2, fj3 = f3. If a category has sums of two objects, then it also has sums of three objects.

(B1 + B2) + B3 is isomorphic to B1 + (B2 + B3).

It also applies to products. In summary, if it is possible to form sums and products of two objects, then it is also possible to form sums and products of families of more than two objects. And a sum or a product of a one-object family should be just that object. The sum of a family of no objects is zero, the terminal object. The product of a family of no objects is one, the terminal object.

Universal constructions

| colimits | limits |

| Initial object (usually denoted 0) | Terminal object (usually denoted 1) |

| Sum of two objects | Product of two objects |

| Sum of three objects, etc | Product of three objects, etc |

Terminal object: in a category, from any other object, there is only one map to terminal object T. The terminal object of the category of sets is any set with exactly one element, and in the category of dynamical systems is any set with exactly one fixed point, i.e. the identity map of any set with exactly one element, and in the category of graphs is one element on top and one element on the bottom, and the only two maps as source and target. And we have 1 x A = A.

Initial object: for each object X in a category, an initial object has exactly one map to X. The initial object in sets is an empty set, and it is also ‘empty’ in the category of dynamical systems and graphs. And we have 0 + A = A.

The product of two objects R and Q is another object P and two ‘projection’ maps P -> R and P -> Q.

The negatives of objects

If A is an object of a category, a negative of A means an object B such that A + B = 0, where ‘+’ means coproduct of objects, ‘=’ is intended as ‘is isomophic to’, and ‘0’ means ‘initial object’.

If A + B = 0, then A = B = 0.

Similar for products, if A x B = 1, then A = B = 1.

Idempotent objects

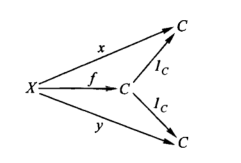

C x C = C. The maps C <-(p1)<- C ->(p2)-> C, taking p1 and p2 both equal to the identity of C we get a product. That means for any object X and any maps C <-(x)<- X ->(y)-> C, there is exactly one map X ->(f)-> C such that the diagram commutes:

such that 1C◦f = x and 1C◦f = y. This implies x = y, so that any two maps from any object to C must be equal. That is: if C <-(1C)<- C ->(1C)-> C is a product, then for each X there is at most one map X -> C. In fact, the converse is also true: if C has the property that for each X there is at most one map X -> C, then C <-(1C)<- C ->(1C)-> C is a product.

And the unique map C -> 1 is a monomorphism.

Solving equations and picturing maps

Definition: E ->(p)-> X is an equalizer of f, g if f◦p = g◦p and for each T ->(x)-> X for

which f◦x = g◦x, there is exactly one T ->(e)-> E for which x = pe.

For any map X ->(f)-> Y there is a unique section Gamma of pX for which f = pY◦Gamma, namely Gamma = <?, f>. The section Gamma is called the graph of f. Like all sections, the graph of a map is a monomorphism, and can be pictured as a special part of X x Y.

Other

cograph, coequalizer